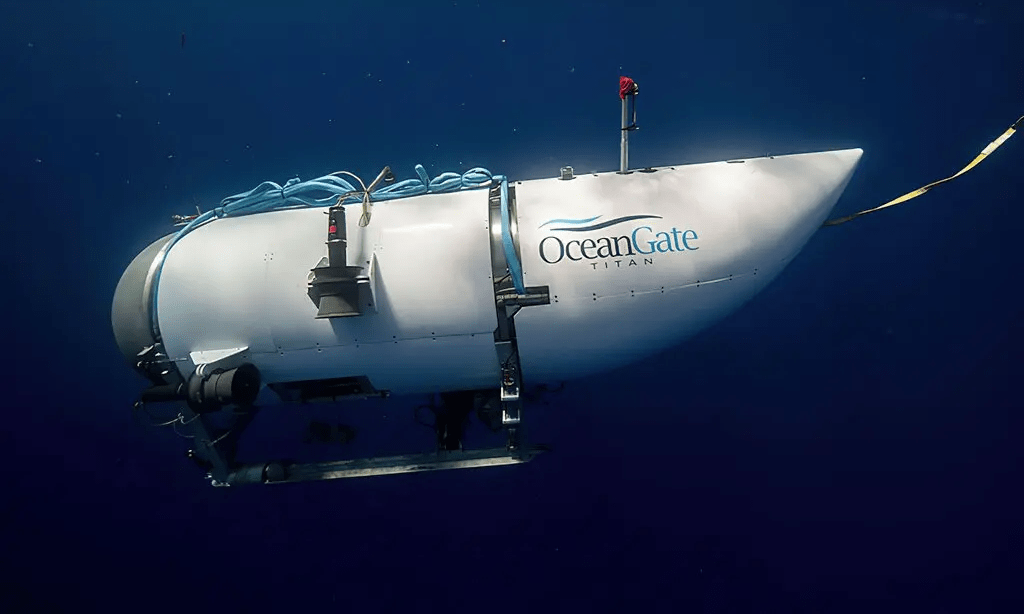

In June, the world was gripped by the disappearance of a deep-sea submersible that was taking paying customers—essentially, tourists—more than 2 miles deep into the ocean to visit the Titanic wreck site. The customers aboard the OceanGate vessel Titan were seeking the adventure of a lifetime, and they had paid handsomely for it.

Videos by Outdoors with Bear Grylls

What the passengers got instead was a real-life version of the terrors outlined in the waiver they’d signed before stepping foot on the submarine. After a frantic five-day search, the U.S. Coast Guard determined that the Titan had in fact imploded, killing everyone on board. The vessel couldn’t stand up to the pressures of the deep.

The debacle raises questions about this type of extreme tourism—the kind in which ordinary people (often ordinary rich people) do extraordinary things, like summiting Everest, going up into space, and diving into the deep sea. Is this ethical? Is it fair? Is it reckless?

Outdoors.com sought perspectives from three people who have interest in and experience with these areas of extreme tourism: high-altitude trekking and mountaineering, space flight, and deep-sea dives. Here’s what they had to say.

Everest, A Playground for the Rich

It was a deadly spring climbing season on Mount Everest, which boasts the highest peak on Planet Earth. Reports suggest 17 people have died on these icy slopes in 2023. Already a sort of frozen graveyard, where doomed mountaineers like “Sleeping Beauty” and “Green Boots” serve as trail markers and somber warnings to those who shuffle past, Everest is certainly not for most.

In recent years, though, it’s become more accessible to anyone who fancies themselves worthy of this hallowed peak—as long as they can pay the price, which can, in some cases, exceed $100,000. Nepal’s government issued a record number of permits in 2023 to people keen to summit. Is this exclusive adventure becoming a bit too accessible?

Gelje Sherpa knows a thing or two about Everest and high-altitude trekking. He was the sherpa who, in May, helped rescue a Malaysian climber from Mount Everest’s “death zone.” Since he began his high-altitude career in 2017, 30-year-old Gelje has summited 13 of the 8,000-meter peaks and remains the youngest person to summit K2 in winter. He’s also led more than 25 successful expeditions to 8,000-meter peaks, including Everest, and he’s participated in more than 50 rescues across several peaks and trekking expeditions.

Gelje makes his living guiding gung-ho climbers to the highest places in the world, but he’s also seen how humbling these expeditions can be, even to those who arrive prepared. So what does he think about Everest’s growing popularity and accessibility?

“The world of high-altitude mountaineering has exploded in the past years, and as [a] guide I have seen firsthand the impacts this has had,” Gelje said in an interview with Outdoors.com. “More and more people are embracing this concept of ‘nothing is impossible,’ mostly because of documentaries that have been released. This, to some people, means turning up to an 8,000-meter peak with no training and no idea of the skills involved. This is deadly. More and more people are involved in accidents because they just don’t know how to look after themselves.”

He suggests that not every person with deep pockets should be able to show up and get a permit to climb Everest—that’s a recipe for disaster. If the number of permits continues to increase every year, it’s possible the number of deaths will increase, too (although, it’s worth noting that most people blame climate change for the high death toll this year).

Another problem is that as demand increases, companies raise their prices, essentially making the trek too expensive for many who are qualified to attempt the climb.

“[The] way it’s looking, yes, it’s just becoming a playground for the rich,” Gelje said. “Everest for sure is getting more and more expensive each year and limiting to people who have had this dream to climb it but could never afford it. [. . .] It’s a huge shame because Everest is such a stunning mountain to climb, but it’s just too overcrowded now, it takes away the beauty of it all.”

“We also have to control how we move forward, potentially being more selective with clients who can receive a permit to climb an 8,000-meter peak,” he added. “This could mean making sure they have already summited a 6,000er before or [passing] a basic test to see their knowledge, et cetera.”

Another way to keep the danger factor in check, Gelje said, would be to limit permits. He doesn’t think this solution would go over very well, though.

“I think the only way to do it is by restricting permits to people who have the proper experience before coming to an 8,000er,” he explained. “However, this is highly unlikely, as it would probably half the number of people coming to Everest, and both the companies and the government would probably not back that idea.”

Gelje believes it’s also important to keep the sport open to newcomers who deserve the opportunity to try to make their dreams come true. In fact, asked whether “ordinary” people should be climbing Everest, Gelje is all for it, as long as they have the right experience.

“Adri, my climbing partner, was an ‘ordinary’ person five years ago, but she trained hard and it was obvious, and now she is a mountaineer,” Gelje said.

Gelje and Adriana Brownlee “Adri” own AGA Adventures, and they help people grow in the mountaineering space and prepare for their dream quests, whether that’s trekking Annapurna Circuit or climbing Everest itself. Between the two of them, Adri and Gelje have three Guinness World Records, 30+ 8,000-meter peak summits, and 40+ mountaineering expeditions under their belts.

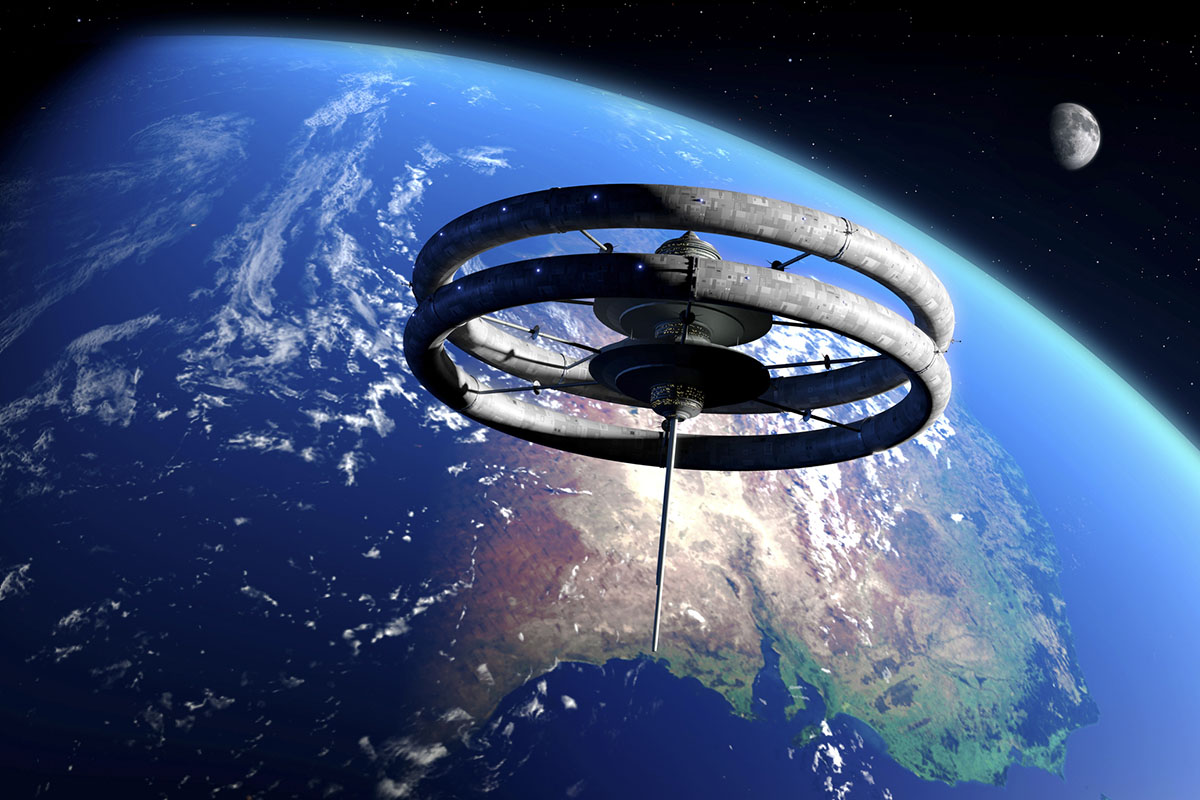

Space, the Final Frontier, Conquered?

Earlier this summer, a Blue Origin rocket engine exploded during testing at a facility in Texas—a harsh reminder that spaceflight is a dangerous undertaking. Blue Origin is Amazon-founder Jeff Bezos’s private space company that has successfully taken paying customers up into space aboard the New Shepard rocket, which is named after American astronaut Alan Shepard.

Dylan Taylor was aboard the New Shepard on December 11, 2021, when he became one of the relatively few humans who have traveled to space—and one of even fewer humans to have traveled to space as a commercial astronaut.

Taylor is a business leader and philanthropist. He is the chairman and CEO of Voyager Space and founder of the nonprofit Space for Humanity. As a cherry on top, he’s also one of the very few who have descended into the Challenger Deep in the Pacific Ocean’s Mariana Trench—the deepest known place on Earth.

As an extreme tourist himself, Taylor is a believer in democratizing the world’s most exclusive adventures.

“I’m in the camp that says space is the next big thing for humanity, that it’s sort of the blank canvas that we have the ability to sort of reimagine what’s possible, treat each other better, have a better civilization, those kinds of concepts,” he said in an exclusive interview with Outdoors.com.

For Taylor, going to space was nothing short of life-changing.

“It is a very profound and transformative experience to see the earth from space, [and] it is very apparent when you’re up there that this is really a miracle that we have here on Earth,” he explained. “The rest of the universe is not like this. So far as we know, it’s cold and dark and hostile, and we have this sort of amazing, beautiful paradise here on Earth that sometimes I think we take for granted. It is very apparent when you’re up there how fragile the ecosystem is.”

Taylor paid a lot of money for this experience (he couldn’t share just how much, because he signed an NDA saying he wouldn’t), but he wants more people to be able to experience what he experienced, and this is something Space for Humanity is actively doing. He believes those who go to space come back with a new perspective on Planet Earth—and a renewed drive to protect it.

“There’s this notion that going to space has this transformative power—the overview effect, if you will—and that’s really a gift that should be shared widely,” Taylor said. “It shouldn’t be just professional astronauts or very wealthy people that benefit from that.”

Space for Humanity’s Citizen Astronaut program fields thousands of applications each year from people who want to become citizen astronauts. They apply in part by outlining how their trip will empower them to be a force for good here on Earth. The program sponsors a new citizen astronaut each year, with the caveat that he or she will work on the projects or initiatives outlined in his or her application upon return.

While Space for Humanity is working to democratize space travel, for the most part, it’s still the realm of billionaires. Is space travel, then, becoming a prestigious feather in a very rich person’s cap?

“I think people have different motivations,” Taylor said. “Some, I think, are legitimately trying to check boxes and go down the list of all the different things you can do. Other people are just, like, in my case, just being super passionate about a lifelong dream.”

“But I think that desire to look [at] what’s over the hill and explore and do things that are unique and challenging, I think that’s sort of been embedded in humanity since the beginning of time.”

While humans’ desire to explore and push themselves to the limits is not new, the technology to take them to new heights—or depths—is relatively new, and, as OceanGate recently proved, technology can fail. Asked whether it’s reckless to take regular people to space, Taylor says no.

“I think it’s risky, and it’s really important that people who do those trips really understand the risks involved,” he explained. “But I don’t think it’s reckless.”

“I think it’s risky . . . but I don’t think it’s reckless.”

Dylan Taylor

In the case of space, Taylor says regulations have kept it a tier or more above, say, OceanGate, but for-profit companies in this realm, in his view, should be investing profits back into making these extreme journeys safer and more accessible.

“Are there operators who are taking undue risk for monetary gain? I’ll leave that to others to decide, [but] in the case of space flight, it’s very tightly regulated, so it’s pretty difficult to do a money grab without crossing some boundaries that regulators would not allow you to,” he explained.

“But I think a lot of these experiences are for-profit, [and] as long as those profits are reinvested back into perfecting the technology and making it more accessible, that’s probably a good thing. I think where it’s not a good thing is if people take undue risks for financial benefit and they don’t disclose what those risks are,” Taylor added. “I think that’s where it crosses the line in my view.”

Into the Abyss

Whether you book a ticket to space, participate in extreme sports like skydiving or big-wave surfing, hike in a national park, or drive to the grocery store down the street, safety is never guaranteed. However, when talking about the extremes of high-altitude climbs, being rocketed into space, and descending to the depths of the ocean, danger is more front and center in the conversation because a lot can go wrong, and, if it does, help may not be available.

For the passengers of OceanGate’s Titan this past June, the chance to see the Titanic with their own eyes was worth the expense and the risk. If the demand is there, can we fault the companies that deliver the supply to meet the demand? Is an occasional disaster just part of human exploration?

Joe Dituri is a deep-sea diver who spent 28 years in the Navy, serving part of that time as a Navy Diving Saturation Officer. He also has a PhD in biomedical engineering and is known as “Dr. Deep Sea.” In June, Dr. Dituri surfaced after a 100-day jaunt living underwater. Dituri was his own test subject in Project NEPTUNE, in which he lived in the Jules’ Undersea Lodge, an underwater habitat in Key Largo, Florida, for 100 days straight, conducting daily experiments in human physiology.

Dituri is a huge proponent of pushing the envelope for human exploration.

“My personal investment in this whole thing stems around the advancement of the human race,” he said in a video call with Outdoors.com from his Undersea Oxygen Clinic in Tampa, Florida. “So, we are advancing humans, we’re going down the road to that next thing that we’re doing. Once we solve this, we cure that. Once we do this, what’s left? Exploration of our galaxy, exploration of other galaxies. Exploration of all the world, right, to find everything that there is to be found. It’s the whole Star Trek thing. It’s to ‘boldly go where no man has gone before.’ But what is this about? It really is about exploration. It’s the only thing that will be left in the end.”

Dituri has traveled nearly 2,000 feet deep in the ocean, but not as a tourist. It was part of his training as a deep-sea emergency rescue unit in the U.S. military. Even still, he says democratizing adventure and exploration is critical, and it’s only reckless if participants aren’t trained and prepared.

“It is important to push the boundaries; nay, it is required to push the boundaries. We go boldly. This is what we do. This is, as a society, what we need to do,” Dituri said. “But, we need to perform risk mitigation. [. . .] When I jump out of an airplane, I have two parachutes on my back. It’s not just one. I always have a backup, and I’m well trained in what could go wrong. So . . . that’s the overall goal. You mitigate the risk down to an acceptable level, with training and education, and that’s what we’re looking to do. That’s the only way to pursue and go forward and basically make meaningful contributions.”

“When I jump out of an airplane, I have two parachutes on my back. It’s not just one. I always have a backup, and I’m well trained in what could go wrong.”

– Joe Dituri, Dr. Deep Sea

Therefore, Dituri does not see the democratization of deep-sea exploration as a money grab.

“The quote from President Kennedy comes up,” he added. “We choose to do these things. We choose to go to the moon and these other things in this century. Not because they’re easy, but because they’re hard.”

“This is the whole spirit of exploration,” Dituri concludes. “We need to gain and gather that knowledge and information . . . so that we can give it to the rest of humanity.”

If viewed through a glass-half-full lens, then, every implosion and explosion equates to some massive lessons learned—it’s one small step for man, one giant leap for humankind, so to speak. Not all extreme adventures that end badly offer up some consolation prize of knowledge or experience, though. Some just rip away a person’s life. Whether that person signed a waiver, handed over a fat check, or simply lived for the thrill, it nonetheless begs the question: Is there such a thing as an adventure too extreme, or are today’s most extreme adventures the proving ground for the next era in human exploration?